First-Hand:Memoirs of Constantino Il Cervo

My Struggle to get Engineering Degrees

It is my hope that the following story, which reflects a part of my personal career, can be helpful for young engineers to show that the life of an engineer is not always easy going. In particular, to give another example of how a specific technological development was turned into business, but also how a technological business stimulated new technological developments. It is also my hope that older engineers with their experiences can find similarities and let us know how they were tackling their problems, in particular dealing with negative attitudes from their environment based on wrong perceptions and how they were able to overcome such obstacles. In my case, it started with the defense of my industrial engineering thesis on magnetic amplifiers and the associated introduction of a working "tracking mechanism" for use on the factory floor.

I had prepared well for my thesis defense and went in confidently. Normally, a defense takes about fifteen minutes. In my case, I was in for about an hour. I sensed something was amiss; I heard sighs and mumbles, and when I occasionally turned away unexpectedly instead of writing on the board, I caught the jury displaying extremely negative body language. They asked some sharp, angry questions, but because I already had a good command of the material, I could tell from the questions that they didn't understand much of it. So, I did my utmost to make my point clear in various ways. My innate respect (or should I say instilled respect?) for professors and jury members prevented me from reacting more sharply. At the end of this hour, the jury chairman issued the verdict: "Sir, it's not worthwhile that you came. In other words, you'll probably come back sometime." I couldn't believe my ears; I was on the verge of a mental breakdown. Two years of intense work, focused on this very subject, only to hear the jury completely did not understand anything, and now I saw my diploma snatched away right under my nose. Surely this wasn't possible. But apparently, it was. I realized I had nothing left to lose. I also realized there was really no point in coming back. Why would they let me pass next time, since additional knowledge would likely be even less understandable for them? So, I said confidently: "Gentlemen, I've worked on this project for a long time, and I sincerely believe I have a thorough knowledge of this subject. What did I say wrong or what wasn't clear?" Surprised by this unexpected reaction, the chairman said: "Perhaps you've studied well, but you copied—or rather, translated—your work from Storm's standard work on this subject. Do you think I'm unfamiliar with this book?" My initial reaction was sharp: "Mr. Chairman, you are allowed to know that much comes from this book, so it's the first important work on my bibliography. Furthermore, you may know all the books I based my work on; they're all listed in my bibliography." The chairman now reacted a little more cautiously and became a bit friendlier: "That's certainly positive, but surely we should also expect an original approach?"

I became more friendly and said, "That's exactly what I tried to explain earlier, but I had the impression they weren't following me very well at that moment." I now made my way to the green table, briefly and convincingly reiterating the key points of my argument, which I had already briefly summarized. The chairman nodded appreciatively, and the rest of the jury immediately joined in. Finally, the chairman said, "Congratulations, sir, you defended your thesis very well." Incredibly, after a full hour, I had failed the exam and passed two minutes later. Later, I heard from my friends that my supervisor and the institute's own professors who were present came out sweating. They told their fellow students that it had been a terribly tense jury exam, and that they had never experienced anything like it.

The defense of my thesis to become a Civil Engineer, on the interaction of magnetic waves in a plasma environment, had nothing to do with my environment but, as you can read further, it created the necessary stress.

The problem with studying plasma was the disparity in the existing scientific literature at the time. It was either almost popularized, or at such a high level that I lacked the necessary background knowledge in physics to understand these works. So, I lacked an intermediate step, a solid introduction to successfully tackle the more complex literature. No matter how intensively I searched, I couldn't find it. The internet didn't exist yet, and the subject wasn't classical enough. During the summer holidays before my final year, I visited the German university town of Göttingen. I enjoyed the summer weather, the beautiful market square, and the picturesque surrounding streets. By chance, I passed a bookstore window, and there, just a meter in front of me, lay a book that I quickly understood was "the missing link." It was the only copy. Just browsing through it clearly indicated that I had a precious key in my hands. I was very excited and bought it immediately. Back home, I couldn't wait another day to thoroughly read it. Now I was indeed ready to understand, process and, above all, apply the other background literature. My assignment was to investigate the influence of magnetic fields on an electromagnetic wave in a plasma environment and, from that, to derive the permissible transmission frequencies (which frequency bands could and could not be used). To do this, I had to formulate a so-called dispersion equation, which means studying the speeds of electromagnetic waves as a function of their frequency, looking for singularities. After months of manual calculations, at a time when computer time was still very precious and visual representations were not yet part of the daily equipment of an engineer or scientist, this was, in fact, a huge gamble. Finally, I had arrived at a certain monstrously complex equation as a result, without really knowing what this result would entail. With mixed feelings, the computer program based on this was taken to the data center where it was entered into what was then a mainframe (a powerful IBM computer, so to speak). I was terrified when it turned out that the only result on the large (and expensive) graphing paper (one meter wide) indicated a simple horizontal straight line. The result was therefore one and the same speed, specifically the speed of light, for all frequencies. Apparently, there were no forbidden frequency bands, the imposed magnetic field had no influence, and the plasma played no role whatsoever. This was obviously impossible. From the literature, I knew roughly what a few simple configurations looked like. After all, the goal was to create added value. For the second time in my engineering studies, I saw my potential diploma slip away. Resignedly, I looked again at this questionable result, which was doubly dramatic, since my compulsory military service could no longer be postponed. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to an inconspicuously small point right at the beginning of the horizontal line. Could something be going on here after all? Could it be, for example, that everything was simply a matter of the correct scale setting? I briefly regained hope; my heart pounded like crazy. So, I took a scale, which I extended from zero frequency to a frequency value that extended no further than a millimeter beyond this last point in my original unfortunate graph. The tension was palpable. Yet, a more than beautiful graph now rolled out of the computer. I could now comfortably continue working with variable magnetic field values. It explained almost everything I could dream of. Then I knew I could complete my thesis successfully.

Introduction

As a student of applied sciences, specifically as civil electrotechnical and mechanical engineer specializing in electronics, I was always fascinated by how mathematical tools could be used to describe and manipulate the physical world using models. It bothered me that I didn't always understand what was happening in that physical world. In other words, what is the consequence of the model, which we ourselves, as humans, ultimately designed, and what happens in reality—yes, what is reality? So, in my so-called positively oriented science, even technologically applied science, I was confronted with a very philosophical question. Speaking of philosophy, I remember that, in the history of this philosophy, there was talk of Nicolaus Cusanus (1401–1464, from Cues in the German Moselle Valley and plenipotentiary of Pope Nicholas V), who concluded that God had created the world on mathematical principles. Now, even if at some point I wondered about the events in the real world, the final results of the calculations yielded very useful, practically usable and measurable results, often with very precise values.

My decision was made I was going to look for a position in an organization where I would have to use highly advanced mathematics as much as possible, but always with the intention of serving as useful material for solving practical problems. I had three options. For practical reasons, I chose the telecom industry, as I wasn't obligated to move and I didn't have any additional housing costs, which would immediately be deducted from my salary. I had two degrees: industrial engineering and civil engineering. Since I was already a bit older, had some language skills, and was naturally quite diplomatic, the chief engineer suggested that, in my case, I was suitable for a very "horizontal" position. This involved implementing a computerized planning system in the engineering department for the development of the new digital telephone exchanges. This provided the opportunity to get to know the company and its departments better. To gain practical management experience, I was also put in charge of a small "circuit design" department. The focus, however, was on the planning system and, as I later discovered, on resolving a vicious circle dangerous for the company: a form of immobility where departments blamed each other for what went wrong. It was clearly a managerial job, where I often felt more like I'd ended up in a courtroom than in a private company. The only background knowledge I possessed was Louis A. Allen's well-known book, "The Management Profession," which I had once read. Nevertheless, I accepted the job because I saw it as a way to somewhat compensate for the later start I had due to my longer studies, since a managerial job as a starting engineer was better paid than a purely technical assignment. When I finally managed to successfully implement the system through a kind of shuttle diplomacy and exposed the mutual games, I was offered a new opportunity after two years. Besides a few specific technical assignments, a vacancy for a teletraffic engineer opened up. My "new" chief engineer (LB) pointed out to me that this job would require a high degree of independence and extensive mathematical expertise. It had actually been about three years since I'd last dealt with complex mathematical applications. In the army, as a topographer,

I'd only performed some trigonometric calculations. In the two subsequent years, as mentioned above, I'd held a more managerial role. The only real mathematics I'd acquired was a theory of graphs, which ultimately provided a background knowledge of the methods used, more as a curiosity than a concrete contribution to the company's operations. It was interesting in that way that it gave me the opportunity, within the framework of the engineering association, to participate in a workshop on applications of graph theory. In addition to the methodology used, I was also able to highlight the managerial aspects, concluding the era of my planning role. Although I didn't make my decision without some apprehension, my initial desire to pursue a position where I could utilize mathematical applications to the fullest was stronger than my fears. I accepted the offer without much hesitation.

Teletraffic

The new position couldn't have been further removed from my first job. Gone were the frequent meetings, gone were the frequent social chats in the various departments to uncover the truth about what was happening behind the scenes. My new boss had warned me: "a high degree of independence and a heavy mathematical background." It was going to be a struggle; I had to master the new, more demanding knowledge and practical application as quickly as possible. During the day in the office, the first small assignments and a major challenging one, regarding the design of the structure of the new digital exchange, arrived. The hardware engineers could consult with their colleagues in the hardware department, the software engineers with their colleagues in the software department. I was alone with my problems. My only support and sound board came from, on the one hand, the parent company in the US and, on the other, from universities in my own country. But in any case, every problem is different, and even with that support, I had to solve the problems presented to me myself. My first participation in the International Teletraffic Congress (ITC), however, was a fantastic experience. The various required domains of knowledge were given a face by the specialists present. Besides the in-depth knowledge of how a telephone exchange works, there was the respective required knowledge from this applied science, including combinatorial analysis, probability theory, queueing theory, etc. I discovered how specialized this field was. At that time, there were three teletraffic engineers in Belgium: one a long-known employee of ITT (later Alcatel Bell); a graduate of the University of Liège who had submitted his doctoral thesis on this subject and became a teletraffic engineer for the Belgian operator; and me, of GTE. My work had not escaped the notice of the Americans, through my regular communication with their specialists. One day, I was asked to go to the USA, specifically in Boston (Road 128, the so-called “technology highway”), to participate in the development of the world's first remotely controlled telephone exchange. Besides supporting the design of the structure of the telephone exchange, I was asked to set up proper industrial worktables and to develop the complete procedures for the installers and operators, so that they could later continue working independently. After completing this project, back in Europe, I faced a significant amount of work. This included providing guidelines to the software group to develop the sizing-pricing program for the entire telephone exchange system, including its remote-controlled exchanges, reliability calculations, availability and maintainability, which in turn determined the "headcount" and the required maintenance personnel at all levels. But also, the calculation of the central processor was now added to my duties. This was the prelude to the topic I want to address. A telephone exchange has increasingly become a large computer system that could no longer be considered a standalone unit. Remotely controlled units had accelerated this process, but the coherence and integration with the rest of the telephone network now also became unavoidable.

Networkplanning

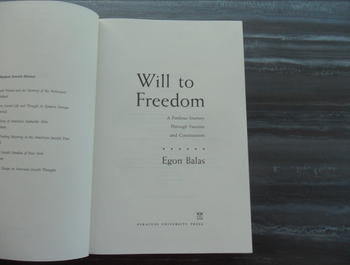

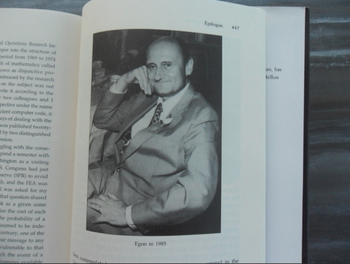

Almost unnoticed, I was given responsibility for a new area of expertise, which in turn required new, more extensive knowledge. I also had to attend the International Networkplanning Congress to stay abreast of developments in this field. Among other things, I had become acquainted with the more scientifically grounded methods of France and Canada. I especially needed new tools for so-called "dynamic programming," especially the 0-1 programming of the Romanian Professor Egon Balas, who later became an American citizen and Professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Much later, I learned that he had written a book about his life, "Will to Freedom," which I highly recommend. He had first fallen victim to the Nazi regime and later to the communist Soviet regime. I thanked him and told him how his scientific work had contributed to my achievements. He then gave me his book as a gift. However, other things also joined the "dynamic programming" family. Integer programming, mixed integer programming, the bankers' present worth calculations—compound interest calculations, so to speak, to account for the long-term current value of money—but then focused on telephone exchanges. Regarding the latter, I still had good contact with a specialist in this field, Mr. Ollie Smidt of GTE Head Quarters in Stamford, Connecticut. He had written a book on Engineering Economics. All of this was interwoven with demographic growth related to the exchanges in question and the necessary "intangibles." This allowed me to support our client, the Belgian telecom operator, then still RTT, for its public networks, as well as the NMBS rail-road system for its private telecom network. At the Belgian RTT, Mr. Ronny David had waged a lonely battle to make it clear that the time for switching only voice connections was over. He later became Chief of Staff at the Ministry of Telecommunications. The director of the telecom infrastructure at NMBS, Mr. De Smet, later became the general manager of infrastructure at NMBS. Both of them had great respect for my work, and I must say the respect was mutual. Naturally, my additional job also brought me into contact with another branch of the parent company and the GTE manager there, Mr. Don Schneck (DS).

Meanwhile, through my contacts with the engineering association and academia, I had been offered a chair at the economics college in Brussels, which focused on the training of government officials, the so-called university of civil servants. I would be covering telematics networks and their applications. During that period, I also organized an international conference on telecom networks together with academics and other people from European industry, to which I naturally invited also the American GTE manager, DS. Also, a Japanese professor spoke at the conference. Thus, Europe, America, and Japan, were represented at our rather limited conference, where I had been appointed chairman (on top of presenting my own paper, that I was obliged to share with my new colleague, to show his presence in the company). This function of chairman was primarily to counter my own company, which, despite all my efforts, was gradually showing a clear lack of respect for me personally, much to the chagrin of my academic colleagues.

I quickly hit it off quite well with the American manager, Don Schneck, and he was eager to gain a European presence for his optimization program. I certainly considered it a typically practical program, but I had my doubts about its scientific basis. In a friendly manner, I challenged him, Don, to optimize the same network using our respective programs. In short, the goal was to set up a cost-effective network that indicated which telephone exchanges, of what size, and what number of communication lines between exchanges should be installed where and in which year, at the least cost. Don took my bet. He had just been tasked with conducting a network planning study for the state of Ohio in the USA. I had agreed with my colleagues in Belgium that I would forward his input data, which he would enter into his program to achieve a result with his system, to Belgium as well. My newly hired colleague, an American named JG working for us, would then enter the input into my system. Don's system was flexible and practically designed, allowing any changes to be entered into manually. He had designed this to account for potential "intangibles," such as government-mandated implantations, so that, despite the system indicating higher costs, they could impose their sometimes politically motivated decisions on the system. This allowed us to impose the temporal and spatial configuration of the result from my system on Don's system, thus allowing for an objective comparison without any argument that the difference might be due to a different definition of the cost function.

Don was astonished when my result proved to be more cost-effective. He stared at the results in disbelief. The Americans, however, have a sense of fair play. Don now respected me even more and suggested we jointly promote the system to operators as an additional, but useful, service. This, of course, is also hoping that GTE would be able to sell more of the telephone exchanges themselves.

The planning system as a service package

Serious attention was now being paid to the "Networkplanning" service. Don’s system, as mentioned above, was practical and flexible, so we continued using it, but now, where necessary, we have made corrections after checking it with the system I had developed myself. I traveled with Don to the former Yugoslavia. Marshal Tito's country, although on this side of the Iron Curtain, still displayed classic communist traits that frequently hampered collaboration. When, with the mediation of the local "Joint Venture" company, we spoke with representatives of the umbrella organization of Yugoslav network operators, we encountered a remarkable story. The so-called leading group of postal services was represented by two women. They sat there indifferently and visibly reluctantly listening to our presentations. Every time we completed a few sentences in English, they were translated into Serbo-Croatian by our contact person from the "Joint Venture" company, who then explained them to the two women. These ladies' questions were then translated into English so we could answer them. This continued for a few days. Don and I wondered what this almost immediately negative attitude meant. That week, we were invited by our local contact company to Belgrade's nightlife district. It was a beautiful restaurant with lots of wood carvings. A small orchestra of four came to bring a serenade to our table. Coincidentally or not—we'll probably never know—the operator's director was also sitting at a nearby table with guests. He kindly approached us and asked if we were enjoying ourselves. We emphatically confirmed that we were. Yes, how could it be otherwise? Pleasant surroundings, beautiful music, and a delicious meal.

The next day, we were back at the negotiating table. The two dour women suddenly broke out into broad smiles. We resumed speaking English to our contact person, so he could translate for them. We were astonished to discover that this was apparently no longer necessary. The two women were now speaking directly to us in perfect English!

What was the reason for this behavior? We discovered that, in a communist regime, long-term state planning is extremely strict and practically impossible to tamper with. The results of our network planning system were seen as a threat to their work and, moreover, as a potential rejection of their achievements. When we explained that this was simply a tool to help them quickly assess the consequences of potentially changing situations—changes that could occur anywhere, for example, due to demographic shifts or new technologies—and that they could always overwrite certain results, they felt relieved and began to show genuine interest in our system.

After a fruitful collaboration, Don stuck with me. Even so, Don wasn't known as the most approachable person at the multinational. Nevertheless, the collaboration was more than just a collegial bond. The aforementioned manager, Ollie Smidt, from Engineering Economics, had an impressive office in GTE Headquarters. He was very pleased that I had been able to gratefully use his book and apply his theory in my networkplanning model. He was very pleased that I was working so closely with Don. He looked quite surprised that, of all people, I wasn't just working with someone like Don during my work meetings in the US but was also invited to his and his wife's home on weekends and took me for rides around Washington, D.C. Ollie was eager to turn Networkplanning into a full-service group. Traveling with Don also meant experiencing a bit of American history. To save time, he brought a picnic. Touring the Hudson Valley with its famous West Point, where almost all the top officers of the American army had received their training, visiting the vineyards and wineries of this valley, including, of course, the tastings, and visiting President Roosevelt's home—they were all exceptionally interesting experiences. That's how I learned that the President already had a television in his time and a "natural freezer" thanks to a large storage facility where enormous blocks of ice were pulled from the Hudson River in winter. I was also fortunate enough to visit the upper floor, where his guests stayed, the great ones of the earth, like the Queen of England, because a few years later, the entire upper floor burned down.

The United Nations and the ITU

During that period, I started working within the company to explore the possibility of intrapreneuring. Meanwhile, Don wasn't holding back either. One day, he contacted me with great enthusiasm and an urgent and important proposal. At the ITU, a branch of the UN in Geneva, there's a group working on the digitization of developing countries. They're working on a case study (specifically, Senegal) that can serve as an example for other developing countries. Don said: "You know enough about the subject, and it's much cheaper to send someone from Europe to Geneva than, for us, to fly someone across the Atlantic every time." I was very idealistic during my student days; I'd taken free evening classes at my university on developing world issues and had even considered going to developing countries as a replacement for my military service. Now, a proposal was put forward that would offer me the opportunity to contribute to some efforts for the developing world. Moreover, I considered working within the UN framework a topic worth familiarizing myself with. Don therefore asked our Belgian management to free up some time for me to meet this UN request. He further argued that this would be greatly appreciated by the UN. Of course, it's an investment at the outset, but when these countries decide to adopt a digital infrastructure, they also need digital exchanges, which could then be established with initial Western government support, allowing these countries to accelerate their economies and create a win-win situation. I knew that Geneva was an expensive city, and in the USA, I had learned to also express my more personal requirements regarding travel and accommodation in a timely manner. This was sorted out relatively quickly and I was sent to Geneva as a representative of our company. With great courage and enthusiasm, I set off for my first meeting, which would take a mere one-week workweek. Due to my already heavy workload, I could barely skim the documentation sent to the company. As a newcomer, I had firmly resolved to remain low-key, to observe and listen carefully, and, above all, to remain discreet. I wanted to maximize this "on-the-job training" to better understand the environment and working methods. I had brought the document that had been sent to me, and there was nothing else for it but to review it late into the evenings at the hotel.

When the first day arrived, it wasn't the truly educational experience I'd hoped for. There had been a polarization, primarily between Italy and the United Kingdom. The document we had received came from an Italian lady. At the meeting, a young, phlegmatic Briton suddenly distributed a different document. The entire day was spent discussing which document to use. This continued for the next few days until the end of Thursday, the penultimate day! The chairman said, "We have one more day. I expect a decision tomorrow morning; if not, we'll proceed to the vote, so we have at least one more day. Because of this situation, a lot of work will have to be done at home now." When no answer was received by Friday morning, the vote was taken. This is where I saw how blocs form. France sided with Italy, the Americans, as traditional Anglo-Saxons, sided with the United Kingdom, and so on until an exact 50/50 split was reached. Each bloc praised the positive aspects of their chosen document and highlighted the shortcomings of the other. The chairman then looked at me and said, "Now I'm curious to hear what Belgium will say." There I sat, determined to keep a low profile. Everyone in the large conference room anxiously awaited my answer. I remember wanting for a moment to hide under the seat and wishing I'd never attended this meeting. Whatever I decided, I was always going to antagonize half the meeting, with who knew what consequences for my company and the multinational. It all raced through my mind. However, I also thought about the days lost and the serious errors I'd discovered in the document that had bothered me. Under pressure, people often get creative. Suddenly, I stood up confidently and addressed the meeting: "Yes, I think I can help here. It's true that the British document is much more structured, it's much more logical," and so on. I continued throwing flowers at the Briton and then continued: "But none of us have had time to read the document, so let's follow the other document." Everyone agreed with my proposal, and no one really lost face. Finally, the work could begin. After the meeting, the chairman came to me and said: "You saved this working group. Your comments show you know what you're talking about, and your way of dealing with people would be very helpful to us here. Would you be willing to play a more central role in this project? I must tell you that this will involve several additional meetings, calculations, and travel in Europe. I noted that several organizations had to decide on this matter: my company in Belgium, the American multinational, and the UN itself. The manager of the ITU-UN, Mr. Maurice Ghazal, a Lebanese Christian, became angry and said: "This problem has been dragging on for far too long. We now have someone with the necessary expertise. Let us now free up the necessary resources to bring this work to a successful conclusion." Don, in the USA, was quite pleased when he received the letter from the working group chair and, in turn, wrote to my Belgian management asking for time so I could work part-time for the UN and provide advice on this project. For three large, normally cumbersome organizations, the whole thing was completed in a very short time. Meetings with the small central working groups, which were supposed to play a leading role, took place in Rome and Paris. The plenary sessions with the full group were held in Geneva. I managed to maintain good relations with the entire group, from the two initial blocks, until the end of the work. Later, during a visit to Geneva during the holidays, I saw our work group's book about the digitization of developing countries in the showroom of the ITU building (the well-known ITU Tower). My colleague and friend, Mr. Paulo de Sousa (an active IEEE member), whom I already knew from the ITC Congresses, but who later worked at the European Commission, where I had also started to work shortly before, also told me that he, together with Mrs. Béatrice Craignou of France Telecom, who had also participated in the ITU project, had digitized the infrastructure of an Asian country.

Increasing instability in the telecom world

It was the 1980s. The telecom world was going through a difficult period, both for the companies themselves, the operators, and, of course, the individual employees. I, too, regularly felt the consequences of these potential shifts, acquisitions, and mergers. The work atmosphere was no longer as pleasant; criticism was voiced more readily, and scapegoats were sought to explain the poorer results. Don had warned me during one of my last visits: "Constantino, I'm telling you this as a friend: get out of GTE, because it's no good anymore." A few of my personal experiences made it clear that things were going wrong. As engineers in a company that adhered to the "all-ranks" philosophy, we were all sitting in a large room with secretaries, technical staff, etc. My line manager came to me, seething with anger, with a memo in his hand that I had written to him and other managers. It addressed a possible adjustment of the telephone exchanges to accommodate alternative routing. These changes allowed for the use of "detours" (similar to road traffic, but with many more possibilities in this technology) if there were busy places in the network that were better avoided. "What does all this mean?" he shouted at me, "what the hell are you doing? Don't you really have anything else to do? What are you wasting your time on?" I said, somewhat surprised by such intensity, that I thought it might be important (during the International Teletraffic Congresses, an entire session was always devoted to this, and I'd also seen opportunities in the US within my own multinational company). My line manager concluded this rather public rant with the words: "Anyway, stop this nonsense." Yes, what must all the other people in the room have thought of me? Exactly one day later, the American project leader CE came to me with the same memo in his hands. I knew Chuck could be very cynical, and when he said, "A nice note you wrote," I thought, "Oh dear, here we go again." So, I very cautiously asked what he meant. He looked at me with an expression of "I wasn't clear?" He said, "I'm telling you what I mean, that this is a very good memo, and your memo is an example of how I'd like to see communication with the US." I was astonished that this was possible, receiving in two days a public reprimand for a memo, and a compliment the next day for the same memo. One of the GTE top managers who regularly traveled to Europe to monitor operations was also in Belgium, and I was asked to give an in-depth presentation on this topic to him and all the managers in our company. My presentation was very well received. My line manager, who had been so negative, was good-natured enough to say that I had done a good job and should be satisfied with my work. Yet, counter-actions were not stopping. I sensed that forces within the company would rather see me disappear. Regardless, I tried, against my better judgment, after learning about a potential intrapreneurship venture in the outside world, to initiate it within the company's context. This meant establishing an independent business unit within the company as a service advisory unit but strongly linked to the company because of a specific type of product support, namely, providing a service (networkplanning). This could function independently as a service provider but could also potentially promote the sale of telephone exchanges. The Vlerick Management School of Ghent University had organized a competition with the challenge of developing a business plan for an innovative company. So, in my case, I submitted an intrapreneurship plan. I was among the twenty selected people eligible to participate in a residential workshop in Ostend on "Innovative Entrepreneurship." I was very surprised that, despite this personal success, my company wouldn't let me participate as an engineer in the R&D department. I thought the opportunity was too good to pass up. I enrolled at my own expense and took time off work to participate. It turned into a more than fulfilling "crash course" for potential entrepreneurs, from which well-known managers have emerged. For me, it was one of those eye-openers that gave me a different perspective on my own field of work, a kind of insight that changes your life forever, after which you never return to your previous approach.

This wasn't the only battle I had to fight. I wasn't really interested in corporate politics, which turned out to be wrong, and sought other avenues where I could still express my ideas. Meanwhile, I had expanded my academic teaching position to other university institutions. Besides my strictly company-related assignments, I also worked on public presentations, wrote papers, and participated in panel discussions. Often as a lecturer, but also as an employee of my company, which ultimately enhanced my own company's profile. I was also appointed a board member of the Belgian Association for Scientific Business Management, essentially the Belgian Operations Research Society, where I was later elected Vice-President. One day, as a lecturer, I was asked to address the telecommunications users' association and provide them with more technically comprehensible explanations of the innovation, specifically the digitization, of the Belgian telecommunications network. The morning consisted of technical and scientifically oriented presentations. The afternoon was followed by the political debate. Now, I had to be very careful with this presentation. As an employee of a company that primarily derived its income from government investments in the telecom sector, I belonged to the group that traditionally carried out assignments for the RTT. I had to handle the then-government operator, that same RTT, with the utmost caution.

At the other end of the spectrum were the computer companies and other large corporations, who were completely unhappy with the government operator's high telecom costs. When the organizers realized what my main profession was, they did everything they could to get rid of me. They had approached my colleague teacher from the computer course, but he was honest enough to say that this topic was outside his area of expertise. If they truly wanted a specialist in their field, they would have been best served with Prof. Il Cervo. Another meeting was convened, during which I reassured them not to take a political stance, but to remain strictly technical and neutral on the subject, outlining various alternative approaches. Fortunately, I happened to have to leave for Geneva the next day for my meetings with the ITU, which RTT was also attending. This gave me the opportunity to inform them, our largest client, of the situation so they couldn't suspect me of double-dealing behind their backs. At that particular conference in Brussels, I essentially had to walk a tightrope between the Christian Democrats, who still strongly supported RTT, and the liberals, who wanted to open the market to private operators as quickly as possible (which is what happened later on). I succeeded, but there were still unforeseen reactions. The RTT and the Christian Democrats were satisfied because I hadn't criticized the RTT (which is what the liberals actually wanted). The liberals were still moderately satisfied, because they found it interesting to hear all perspectives and the associated opinions. Completely unexpectedly, however, I received the most support from the socialists because they felt my explanation had actually created jobs. This immediately gave me a certain notoriety, even in the political world (which I preferred to stay out of).

I'd like to mention in passing that at that time, the atmosphere in the telecom world was extremely tense, and some things were hitting a nerve, especially because the so-called contract of the century was approaching. This meant the allocation of government funds to companies potentially participating in the new infrastructure. Within the company, after heated discussions with management, I made it clear that optimizing operating profit, taking into account the government-imposed price per line, was no easy task. After a few clear (anti)examples, they understood that they should consider my advice to use demanding non-linear dynamic programming. I mention this to clarify that I still had other ongoing assignments outside of network planning, which certainly didn't lighten my workload.

A turbulent end to my industrial career

As a more or less well-known figure in the telecom world, as a lecturer (but also through my position at the "Belgian Operations Research Society"), I was asked to join the deregulation commission for telecommunications of the Flemish Scientific Economic Congress.

Before delving into this in more detail, and for a better understanding of my contribution, I must briefly address a specific problem the company faced. The latest Stored Program Controlled (SPC) systems, the digital telephone exchanges of the 1980s, were designed to serve a much larger number of subscriber lines. Remotely controlled units were also installed in these types of exchanges. The problem, however, was that even with a very limited number of lines, the central processor became unacceptably overloaded. In other words, the processor's Real-Time (RT) utilization never reached the anticipated capacity to serve the normally planned maximum number of lines. It really didn't look good. The design flaw causing the problem was "undetectable”. It was determined that the maximum capacity of the exchange would be limited to approximately 10% of what was planned; in other words, the exchange became unsellable.

Because of my experience with the previous system, this problem was also presented to me. The key question was: What was the cause of this problem? What type of call and associated processing was at the root of it, what technology, and in which part of this complex exchange was the problem? The lab couldn't figure it out. I tried to have as many measurements as possible taken of a wide variety of processes. It was a difficult task, because even in a new exchange, you have to consider several existing technologies (for example, the existing communication lines with other exchanges). How could I implement the separation so I could see the impact of a specific call type or a specific process?

During a workshop at Ghent University, the topic was "Systems Research." This discipline, and more specifically the topic of non-parametric systems, had just left basic research, and the first potential applications were emerging, albeit with difficulty, into the domain of applied sciences. The plan was for the morning that the presentation was going to be given by Professor Klir of New York State University (then considered the "Einstein" of the field) to explain the underlying theory, and the afternoon the presentation was to be given by Dr. H.J. Uyttenhove to present a few more practical case studies. However, Professor Klir spoke nonstop for five hours, leaving only a few hours for the applications. Next to me in the auditorium sat a former fellow student who had become a teaching assistant. I always found him to be a very dedicated person. After the morning presentation, he said to me, "Constantino, I don't know what you think about this, but I didn't understand a word of it" (apparently, most of the audience didn't understand much of it either, as most of them fell asleep). I replied, "Neither did I." I eagerly awaited the afternoon session with the applications. Due to the short duration, the speaker did not have much time to contextualize the “case”. After the afternoon presentation, my former classmate said, "Sorry, I still don't get it." I replied, "Well, I don't know yet, but I think I'm starting to understand where they're going with this." Having been saddled with a serious problem at the company, I frantically searched for methods or tools that could help me discover the critical error in the exchange. Thanks to the application, I understood that this involved a method not tied to specific functions or statistical models. I rushed to the speaker and briefly explained what it was all about and why I thought his system might be able to help. "I'm not sure I can help you," he said, "because it requires a lot of input data, but come on over, I'm willing to try." So, shortly after, I went to Eindhoven (Netherlands), where his company was located, with all the data I could gather. However, it wasn't very much, because at that point, it was only a lab model. My linear regression analyses and multiple regressions had yielded no results because, as described above, I had difficulty figuring out which split I should implement to select the correct call processes, which would soon paralyze the central office. Mr. Uyttenhove, somewhat uncertainly, presented the results of his system. "I'm not sure if this is the problem," he said, "because I warned you that this system normally requires much more input data." Back at my company, I restarted my regression analyses as quickly as possible. This time with the split of the call processes as suggested by Professor Klir's system. The result was incredible. My regression analyses pointed irrefutably towards one specific process (the jewel of software development, mind you, and therefore, until then, virtually unsuspected). Two weeks later, my findings were confirmed in the laboratory, and the error was corrected. I then gained great awe for this "Einstein" of Systems Research. How, from an unimaginably chaotic mass of basic data, in which no sensible person would detect even the slightest structure, one can gradually build a structure based on entropy, complexity, and quality, which, moreover, provides an accurate picture of what happens in the real world, made a deep impression on me.

Since this method is generally applicable, I applied it as an economic model on the Belgian telecom network. At some point, I received all the input data from all competing participants, under the condition of confidentiality. The model and the results were described in a paper for the Flemish Scientific Economic Congress. This model provided the government with the opportunity to bring all the stakeholders together and discuss a solution. The working group's findings contributed to the European Commission's Green Paper.

That year, I accomplished three things: On company level in response to a request from our Director General to all company staff members, to contribute within the theme of "Mission and Values." I had written an article, a so-called "Tutorial," a didactic piece in which I provided an extensive explanation of model making as a design tool. Nationally, I was able to present my work to the Flemish Scientific Economic Congress (VWEC), where I was elected as a member, secretary, and ultimately co-presenter. Internationally, I had written a paper for the prestigious "North Holland" series, in which my contribution to the Como Seminar of the ITC (International Teletraffic Congress) was published.

Then everything took a turn for the worse. I was no longer allowed to attend the ITC Congress, for which I had registered. They sent someone from the marketing department to the networkplanning conference, and the attendee from our company wondered why he had to go, knowing nothing about it, while I, the specialist, wasn't going. When I was interviewed for the weekly magazine Trends, due to my role in the VWEC, which was actually very positive for the company, I was very annoyed that I wasn't getting a coach for such an important occasion. For my "Tutorial," the young engineers in the company came to thank me because it had helped them so much in gaining more insight into this subject. I was going to give a presentation to everyone in the company's multipurpose hall. The day before, I received a call from the human relations manager, who informed me that the hall was booked for an important management meeting. When I went out of curiosity at the appointed time of my presentation, accompanied by an interested young engineer, we found, as expected, that the hall was deserted. When my annual review arrived, it was made clear to me that I hadn't actually achieved anything. This became too much for me, and I told my direct supervisor that the review was pointless, so I left. Just to be sure, I went to the HR department to make sure I was in compliance. The junior employee said he understood and that I could safely get some fresh air. Then I realized I was on the redundancy list. In stead of my long expected (and promised!) promotion, I was dismissed in humiliation, as belonging to the group of the company's lowest-performing employees.

Fortunately, I received strong support from the academic community, especially from the dean of the “Engineer in company management” Department LG (Prof L. Gelders), University of Louvain, who also served on the board of the Belgian OR Society, from Prof F. Broeckx, University of Antwerp UIA, from Prof R. Van Dierdonck, dean of Vlerick Business School, Ghent, from Prof M. Despontin, University of Brussels VUB, from Prof Chr De Bruyn, Université de Liège. I got also direct or indirect support from C.E.O.’s from important big companies (Pol Descamps, Barco industries, Karel Vinck, Bekaert; Etienne De Wolf, Agfa Gevaert (AG), also from the head of the computer department of AG, Jozef De Kerf. Important support was also given by Mr. Lars Ackzell (ITU), Mr. M.K. Mooney (ITU&BT-British Telecom), Mr. Lars Engvall (ITU), Mr. Ronny David (Ministry of Telecom, Belgium, Mr. De Smet (NMBS, Belgian railroad system), Through Prof. Gelders, I got a coach, who, in turn, also assigned a lawyer to me with a specialization in legal issues for business companies. The lawyer encouraged me to take the company to court, given the blatant underpayment of severance pay. Three judges subsequently ruled that this type of unfair practice against former employees had to stop and severely condemned the company.

After wandering around the Netherlands, where I was able to return to work, encouraged by my coach, I also applied for vacancies at the European Commission, where I ultimately became a selection laureate, as they call it, and was able to further improve my position.

A short acquaintance with spying and human nature

Immediately after I was fired, being at home, my wife noticed that there was a white car in our street close to our house. I was applying regularly for a new job. If I left at 9h, 9:30h, 10h, or at whatever moment during the day, the car left always about 5 minutes later. So, this was a spy, observing what I was doing. A real thriller experience, certainly under the given conditions, this provided extra stress.

I decided to inform the head of the local police department. He made an appointment with me how to tackle this problem. He asked to inform him when this person showed up again, so that he could take note of his identity. Afterwards you will normally not see him anymore, he added. He played it fantastic. When we called him during the next spy session, the head of the police parked the police car far from our house, walked calmly at the other side of the street, then suddenly made a turn of 90 degrees and asked his papers. It was nice weather, during that day in September, but suddenly the windscreen wipers started to work and when he lit a cigar, I saw a flame reach the roof of his car. So, the guy was incredibly nervous. After he showed his documents to the police officer, he drove away like hell. As the head of police predicted, I never saw him again. Due to the privacy law, the police officer was not allowed to disclose his identity, but he came from the community next to my former company. This shows how uneasy they felt about what I was doing, certainly what I found out afterwards at the European Commission, about their way of dealing with former coworkers, I could understand their unrest.

My wife and me learned a lot about human nature. In that same period short after my dismission, people turned their backs to us, as if we suffered from pest or cholera.

Later on, coming back from the Netherlands and joining the European Commission, people came to invite us everywhere to drink coffee and getting invited for dinner, asking if I could do something for their children or even themselves. I told them that they could do like me and react on the EC-advertisements in the newspapers. My former company invited me to come to visit their stand at the main technology fair of Belgium, where I was treated like a VIP.

The European Commission and the end of my active career

The European Commission was more than just a typical experience for me. However, I want to limit my description to the subject of this story. When I was first recruited, it was actually a little too late to prepare for the annual audit of the research projects. My direct supervisor was a Frenchman, RG. Roger, someone I got along with well. One day, he rushed into my office with the words: "Come quickly, Constantino, the audit is about to begin." I protested, saying that it was too early for me to participate and that I first wanted to familiarize myself with both the content of the projects and the audit procedures. He waved away my objections and exclaimed: "You know more than enough about the subject. Come along, you'll have fun." With mixed feelings, I followed him to the audit room, where he invited me to sit next to him at the Commission table. Indeed, it didn't take long for me to understand why he was so insistent that I had to come along. While the Commission chairman was giving a stern lecture to the project leader of the largest consortium participating in the audit, responsible for infrastructure development: "Look, during last year's audit, we issued a stern warning that the crucial networkplanning section was still missing. Why is this still not in order?" The man stood there, bewildered and embarrassed, and said that this expertise wasn't available within the consortium. Roger quietly told me I could also ask questions and speak up. This was indeed a good opportunity to join in the conversation. I said: "If you don't have your own specialists, can’t you find them on the market?" He didn't know that I was a specialist in this field and an employee of a company that belonged to his consortium. Now I continued: "This is taxpayer money; don't tell me it can be this hard to find the necessary expertise in Europe." Roger was clearly amused at my intervention. But what was happening here was actually scandalous. This was what had happened behind the scenes. The company had accepted government funding to carry out this task, likely to use it to cover day-to-day operating costs, while the engineers skilled in the field, for whom the investment was intended, were laid off, leaving users, who were entitled to a broadband network they ultimately helped pay for with their taxpayer money, remaining unserved.

Years later, when I was asked to become a crew member at the Commission's stand in Geneva at Telecom 95, it was an opportunity for me to meet many old acquaintances. At Telecom 99, I not only had to be part of the Commission's stand again, but I was also invited by the ITU to participate as a VIP at the development summit, representing the European Commission. The UN apparently hadn't forgotten my contribution to digitization efforts for developing countries. Yoshio Utsumi (Japan) was the Secretary-General of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and came to greet us. During the audience also the Secretary-General of the UN, Mr. Kofi Annan, thanked us, as invited participants at the development summit, for our contribution to this conference and our support in pursuit of a constructive dialogue between developing and developed countries.

A couple of years later, I spoke with the UN manager who had recruited me, who, full of praise, told the organizer of Telecom 99 that I was the man who had helped them successfully complete a difficult task and, moreover, that I was the only person who had come to thank them for their trust.

Epilogue

As a retired official, I still did (and do) some voluntary work related to issues that highlight serious problems of our society, in particular sustainable development (Club of Rome), technology and society (KVIV), geo-politics (VIRA), and last but not least is my focus on complexity and multidisciplinary problems, which I consider as my main mission now. We need to discover the pitfalls of our own disciplines, especially as engineers serving the rest of our society with our artefacts, we need to bridge the different worlds of our formal education. We need to try to get a deeper insight in what we are doing consciously but also unconsciously. A work that I started in fact already during my last active EC-years where I got the pleasure that it was appreciated by many co-workers and managers in- and outside the EC. We need to overcome the growing danger of a memoryless society and a lack of mutual understanding, sometimes with dramatic consequences. As an example I will stick however to a more light-hearted story. If we want to have a better understanding of where we are going, we firstly need to understand the historical context. We need to take into account continuity AND change. This is in particular also valid in networkplanning business.

When I was appointed secretary and later one of the speakers for the Telecommunications Deregulation Committee of the Flemish Scientific Economic Congress, I was occasionally invited to give presentations on this topic. I remember that during one of these presentations, I deliberately deceived my audience, intending to provide more insight and highlighting the fact that, although technology is evolving rapidly, the reasoning behind the underlying regulations often shares a common thread. It ended up being me presenting the deregulation related to the digitization of telecom infrastructure, as it occurred in the 1980s. When I read part of "my" article aloud, they were positive, feeling that I had understood the situation well and had clearly articulated it. You can imagine the surprise, followed by a hilarious atmosphere, when I informed them that this was not my article at all, but an old article from the early decades of the 1900s, when the telephone infrastructure was put in place.